Every child should have a loving, secure home, but when it comes to housing, children get a raw deal.

Thousands of children are living in temporary accommodation, including many in emergency ‘B&B’ style accommodation for longer than the statutory six-week limit1 – and they are paying the price of this disruption and instability in their educational outcomes.

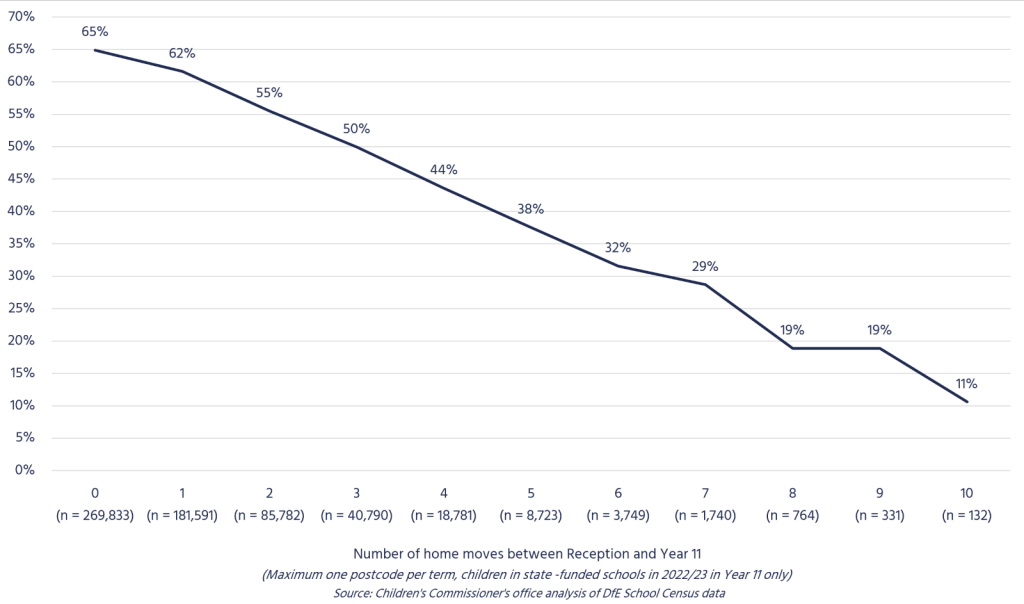

Today I’ve published new evidence showing the more times children move home between Reception and Year 11, the worse their GCSE results. There is a direct correlation – and it is stark.

The analysis uses Department for Education data on pupils’ postcode changes and GCSE exam results. The findings, for pupils in Year 11 in academic year 2022/23, show that pupils whose home postcode never changed between Reception and Year 11 were those most likely to get five GCSEs passes, including English and maths, with 65% achieving this.

Pupils with less stable housing did less well: just half (50%) of those with three home moves over their school career achieved 5 GCSEs including English and maths; and just over one-in-ten (11%) of those with ten moves.

Figure 1: Proportion of children who passed 5 or more GCSEs, including English and maths, in Year 11 by the number of home moves across their school career

The reasons for moving frequently will vary, and many factors influence exam results, but this is concerning, especially as over 75,000 pupils – 12% of all those in Year 11 – had moved at least 3 times.

The role of schools

I shared this analysis with social housing campaigner Kwajo Tweneboa and Sky News, who have been looking at the effect of housing shortages on children and families. Together we visited Surrey Square Primary School in Southwark, where 25% of its pupils are in temporary accommodation. It takes extraordinary steps to support these children and their families, in particular, through the relationship its Family and Community Coordinator, Fiona Carrick-Davies, builds with them.

During this visit, the pupils at Surrey Square told me about waiting years on housing lists, only to be moved into places that are mouldy, full of vermin or otherwise unsafe. Many share bedrooms with their whole families, or sleep on the floor – they told me about doing homework on their laps, stretched out on the floor, or being unable to shower in their own homes. Almost unanimously, they agreed that living in this kind of housing made them embarrassed or ashamed – and that they could never bring friends home.

Great schools like Surrey Square are stepping up and finding bespoke solutions for their families – but it cannot be down to them alone. I’ve long called for schools to become the fourth statutory safeguarding partner, because they know their ‘at risk’ pupils and can help shape local health, social care and policing decisions. I’ve recently carried out a comprehensive survey of schools and colleges in England using my statutory data powers to ask how many of their children live in unsuitable housing, so that we have a clear picture of how housing instability affects children more broadly. The findings will be published over the coming months.

Children in unstable housing

These children’s stories are shocking – but this is what poverty looks like in 2025. They are not isolated experiences. Households with children are more likely than adult households to live in a cold home or have damp in their home.2 Children are also the age group most likely to be overcrowded, with one in six living in overcrowded conditions, or 1.9 million children in England.3

Children’s responses to The Big Ambition survey were clear that poor housing and homelessness are unacceptable. When asked what the government should do to make children’s lives better, three of the 100 most common words mentioned in written comments were ‘home’, ‘homeless’ and ‘house’.

“Make sure all children have a roof over their head and a loving, supportive family around them” – Girl, 11.

“Find homes for homeless children.” – Girl, 8.

Housing is central to children’s lives and a major determinant of their wellbeing. The theme repeatedly emerges in the course of my work when exploring other issues. Parents, children and professionals share shocking examples of the nature and impact of poor-quality housing on children. My report on waiting times for assessment and support for Autism, ADHD and other neurodevelopmental conditions is one example:

“We had 4 different houses over 2 years. Disgraceful houses: rats, abusive neighbours, leaks… My daughter had to go on inhalers because of the conditions in one house. A roof collapsed, foundations collapsed. We had to go into a hotel over Christmas one year.” – Parent of autistic girl aged 13.

Vulnerable looked-after children subject to deprivation of liberty orders told me about their housing situations, including unsuitable unregistered children’s homes, Air BnBs and other inadequate conditions:

“It was just a horrible scruffy little council house. It was an emergency placement […] My bedroom light didn’t turn on, my door didn’t shut” – Child subject to a deprivation of liberty order, 15

Poor housing conditions are a blocker to achievement in other areas of children’s lives. One social worker interviewed for my report on the purpose and content of children in need plans explained that:

“The level of poverty that I’ve seen – [including] housing issues – is such a limiting, frustrating, horrific barrier to achieving the transformative change that I’ve come into social work to try to achieve alongside families” -– Social worker.

Another aspect of poor quality housing is instability. Some families are forced to move, often meaning children must move school at short notice, partly due to the lack of protection for private rented sector tenancies. My office explored this through new descriptive analysis of Department for Education administrative data on pupils’ postcode changes and GCSE exam results. The findings, for academic year 2022/23, show that non-moving pupils (pupils whose home postcode never changed over their school career) were the group most likely to pass 5 GCSEs including English and maths, with 65% achieving this. Pupils with less stable housing did less well, with less than half (49%) of those with 3 moves achieving 5 GCSEs including English and maths, and only one-in-eight (12%) of those with as many as 9 moves. The reasons for moving frequently will vary, and many factors influence exam results, but this is concerning, especially as large numbers of pupils moved at least 3 times: over 28,000.

Children are ambitious about a future that is free from poor quality housing and homelessness. When it comes to housing, decision makers must place children – not just adults looking to get onto the housing ladder – at the centre of their thinking. We must find ways to reduce the squalor, instability and overcrowding too many currently experience, so that all children have a chance to succeed.

Methodology

The office’s analysis uses data from the Department for Education’s (DfE) School Census, which collects pupil-level data from state-funded schools, nurseries and alternative provisions once in each of the Autumn, Spring and Summer school terms. As part of the School Census, schools report to DfE the home postcode of every child on their roll. The office identified 612,352 pupils who were in Year 11 the Summer term of academic year 2022/23, and looked at the number of unique home postcodes recorded against them between Spring 2011/12 – when the majority were in Reception – and Summer 2022/23. Autumn 2011/12 was excluded due to a large number of missing records for this cohort in that term, possibly because many hadn’t yet started compulsory schooling.

This analysis will not capture every home move a child had. Because the data is only captured once per term, the data will not detect two home moves if they occurred in the same term. And, because the analysis looks at postcodes only, rather than the full address, home moves which stay within a postcode area will not be detected by the analysis.

Some children had experienced more than 10 home moves between Reception and Year 11, but were excluded from the analysis as their sample size was insufficient.

This data was joined onto the final version of DfE’s pupil-level GCSE data, and used DfE’s derived variable for whether a pupil had passed 5 GCSEs, including English and maths.

1 Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Tables on homelessness, accessed March 2025. Link.

2 House of Commons Library, Health inequalities: Cold or damp homes, 2023. Link.

3 National Housing Federation, Briefing: Overcrowding in England, 2023. Link.