Children understand the importance of being at school. Thousands of the children I have spoken to in my four years as Children’s Commissioner have told me about the value of their teachers, the things they like studying and the things they want to do after school. In my first major survey as Commissioner, The Big Ask, this generation of children told me that being in school and getting a good education was an overwhelming priority, especially in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

That has not changed – it has been a theme running throughout my work with children since that first survey. That’s one of the reasons why it’s also my overwhelming priority. School attendance is still not back to where it was prior to the pandemic. That’s a worry for me because – as children themselves would attest – school is a unique, valuable component of childhood. It is an institution which illuminates children’s lives not just with education and learning, but with social skills, new experiences and activities, and to make friendships.

So it is really concerning that evidence suggests the level of disengagement from school has scarcely recovered since its peak during the pandemic. Data released today shows that 17.8% of pupils were persistently absent – that is, missing at least 10% of school – in the Autumn term of academic year 2024/25.i Although this is an improvement from the 19.4% of pupils who were persistently absent in Autumn last year, it is still substantially higher than the pre-pandemic figure of 10.9% in Autumn 2018/19.ii

Perhaps more concerning, the proportion of pupils who were severely absent – missing at least 50% of school – has almost tripled since before the pandemic, and has increased every year since: from 0.7% of pupils in Autumn 2018/19, now up to 2.0% in Autumn 2023/24.iii

Much has been debated about the impact of the pandemic on children’s lives, especially having just marked five years since schools were asked to close. It was a challenging time for everyone, and it was only through a spectacular effort by the country’s public servants – not least teachers – that services were able to maintain some level of normalcy. However, while the disruption of lockdown ended and routines returned to more recognisable patterns, children have not yet returned to school at the same levels that they once did. It is worrying how many children – especially those with additional vulnerabilities who may find it harder to attend regularly – are being left behind in the post-pandemic recovery, in particular how many have been allowed to become disengaged from education as they move between primary and secondary school.

It is not just a concern for me, but also for school leaders – many of whom, at the time of writing, are taking admirable steps to make sure their children are prepared to return to the classroom in September, with a focus on those with additional needs to support or who begin as a new Year 7 pupil.

Next month, as the summer break ends and children return to the classroom, I will be publishing a ‘state of the nation’ of England’s schools, using the wealth of data from my School and College Survey, to which nearly 90% responded. It will highlight the biggest areas of concern for school leaders and demonstrate how prominently attendance features. They, and I, do not see attendance as a single issue for individual schools, but as a societal one that requires different support agencies to work closely together to identify and overcome barriers in a child’s life early.

That must include the creation of a Unique ID for every child – something I have called for urgently and repeatedly, and which is being taken forward through the Government’s Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill in this Parliament. Done well, it will prevent any child falling through the gaps in services and becoming invisible to the professionals responsible for protecting them.

If we want to give children the best start in life, it must begin with making sure children can take-up their right to education. Everyone must make school attendance and engagement with education our absolute priority.

School absence spikes in Year 7 – analysis:

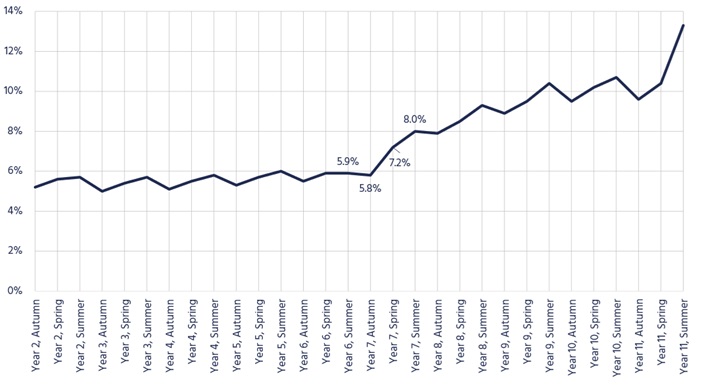

The Children’s Commissioner’s office has undertaken analysis to understand when during their school careers children begin to disengage from education, and so when action and intervention is most pivotal. Figure 1 shows the absence rate of children between Year 2 and Year 11, in each of the three school terms Autumn, Spring and Summer, in 2023/24.

What immediately becomes obvious is the spike in absence in Year 7. Children at the end of Year 6 missed 5.9% of school, broadly comparable to the absence rate across all of primary education. At the start of Year 7, the absence rate was slightly lower, at 5.8%; however, by the Spring term, the absence rate of children in Year 7 had skyrocketed to 7.2%, before raising even further to 8.0% in Summer at the end of Year 7, and never recovering over the remainder of secondary education. This implies that school disengagement starts approximately mid-way through Year 7.

Figure 1: Absence rate across state-funded school population, by year group and school term, 2023/24iv

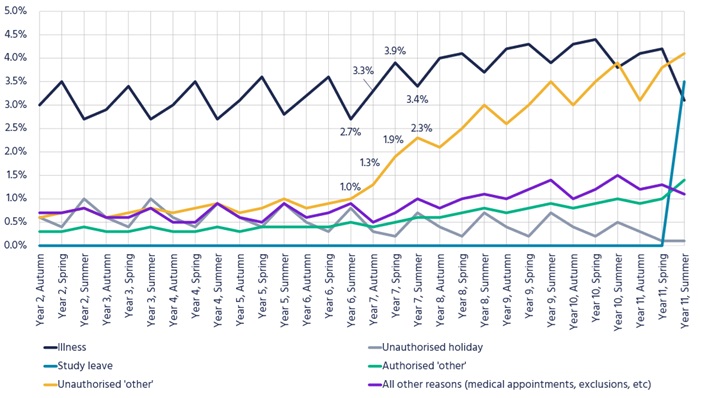

However, Figure 1 does not tell the whole story. Figure 2 expands on Figure 1, additionally showing the reasons children were absent, and reveals the cause of the jump in absence rate between Year 6 and Year 7. Most reasons plotted in Figure 2 are comparably prevalent between Years 6 and 7; however, immediately in the Autumn term of Year 7, absences for unauthorised ‘other’ reasons begin to creep upward. Children in the Autumn term of Year 7 had an absence rate of 1.3% for unauthorised ‘other’ reasons, higher than at any point across all of primary education.

Absences for unauthorised ‘other’ reasons climb across all of Year 7, reaching 2.3% by the Summer term, and generally continue to trend upwards across all of secondary education.

In fact, overall absence appears to spike in Spring of Year 7 rather than earlier in Autumn only because of illness absences. Illness absences are highest for every year group in the Spring term of each year (the Spring term starts in January, in the middle of winter). As a result, children in the Spring of Year 7 suffer from both the annual peak of illness, as well as the increasing uptake of unauthorised ‘other’ absences. Figure 2 reveals then that the real driver of the absence spike in Spring, unauthorised ‘other’ absences, is already developing in the first term of the school year.

Figure 2: Absence rate across state-funded school population, by reason for absence, and by year group and school term, 2023/24v

The unauthorised ‘other’ reason for absence is intentionally a catch-all – there is nothing in guidance which elaborates on where these children might have been.vi Crucially though, these are unauthorised absences, they represent cases where a child is away from school without the school’s permission. If these absences are growing from the very start of Year 7, it implies that school disengagement begins not long after children return from the Summer holidays.

In part, this is not surprising. The transition from primary to secondary is a well-known challenge in education which exacerbates children’s existing vulnerabilities, and the Children’s Commissioner has published extensive evidence on the consequences of poorly managed transitions.vii,viii However, given this wealth of evidence, it is disappointing that the transition to secondary – and secondary education itself – is failing to create an environment where all children are able to attend.

Fundamentally, 17.8% of pupils are currently persistently absent – roughly 1 in 6.ix That is absolutely unacceptable. Not only must we do better but, as the pre-pandemic figures show, doing better is unmistakably achievable. The Children’s Commissioner wants to see the government introduce a Unique Child ID for every child, and a Single Child Plan for every child which needs one, to make sure no child can fall through the gaps, and so that services stand ready to respond promptly as soon any child needs any support for any additional need.

[1] Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2025. Link.

[2] Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2025. Link.

[3] Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2020. Link.

[4] Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2025. Link.

[5] Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2025. Link.

[6] Working together to improve school attendance: Statutory guidance for maintained schools, academies, independent schools and local authorities, Department for Education, 2024. Link.

[7] Lost in Transition: The destinations of children who leave the state education system, Children’s Commissioner, 2024. Link.

[8] Children Missing Education: The Unrolled Story, Children’s Commissioner, 2024. Link.

[9] Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2025. Link.