Covid-19 has increased many of the risks facing teenagers. Not just in terms of the epidemiological risk, but also in terms of the additional risks that the lockdown itself has created, such as an increased risk of poor mental health, exposure to domestic violence and addiction in the home, and exposure to exploitation. These risks have been exacerbated by the closures of schools, youth services, summer schemes, parks and leisure activities; reductions in mental health support; and the increased strain on families.

The effects of this will have been particularly acute on the teenagers who were already vulnerable before Covid-19, especially those who were falling through the gaps and being missed by local services. With schools closed to most teenagers for half a year, and face-to-face children’s social care provision being curbed, these teens risk becoming even more ‘invisible’ than before.

This report assesses the number of teenagers in England, and in each local area, who were already vulnerable and falling through gaps in the education and social care systems before Covid-19. The risks focused on here – such as persistent absence from school, exclusions, alternative provision, dropping out of the school system in Year 11, or going missing from care – are important signals of children at higher risk of future educational failure and unemployment, as well as of falling into crime and criminal exploitation.

There is an urgent need for local agencies – councils, schools, youth workers and police – to focus resources on teenagers at risk of becoming ‘invisible’ to services or who have gone missing under lockdown. These teens are easy prey to criminal gangs and abuse, and are at very high risk of becoming not in education, employment, or training (NEET). Ensuring that they are able to recover from the crisis and have a way of getting back into education, training or work is vital.

To address this, the Department for Education, schools, LAs, police forces and safeguarding partnerships need to work together on a plan to identify, track, support and ultimately re-engage these children.

There is also a need to prioritise summer schemes – including sports clubs, play schemes, holiday clubs and youth clubs – which give young people a range of safe, positive, structured activities to take part in, led by trusted adults and role models. To make this happen, the government must work with local areas to remove any barriers to delivering these schemes. It should also advise schools to support these schemes from within their additional £650 million ‘catch up’ funding.

Key findings

Large numbers of teens have multiple needs. Using the latest data available to us, we find that in 2017/18 nearly 480,000 teens aged 13-17 met at least one of the following criteria:

- Any identified special educational need or disability (SEND)

- Any Child in Need (CIN) referral/episode during the year

- Any fixed exclusions during the year

- Any permanent exclusions during the year

- High levels of absence during the year (missing at least 15% of school)

- Any time at a pupil referral unit (PRU) during the year

- Dropping out of the school system in Year 11

- Missed at least an entire term of school in the last two years

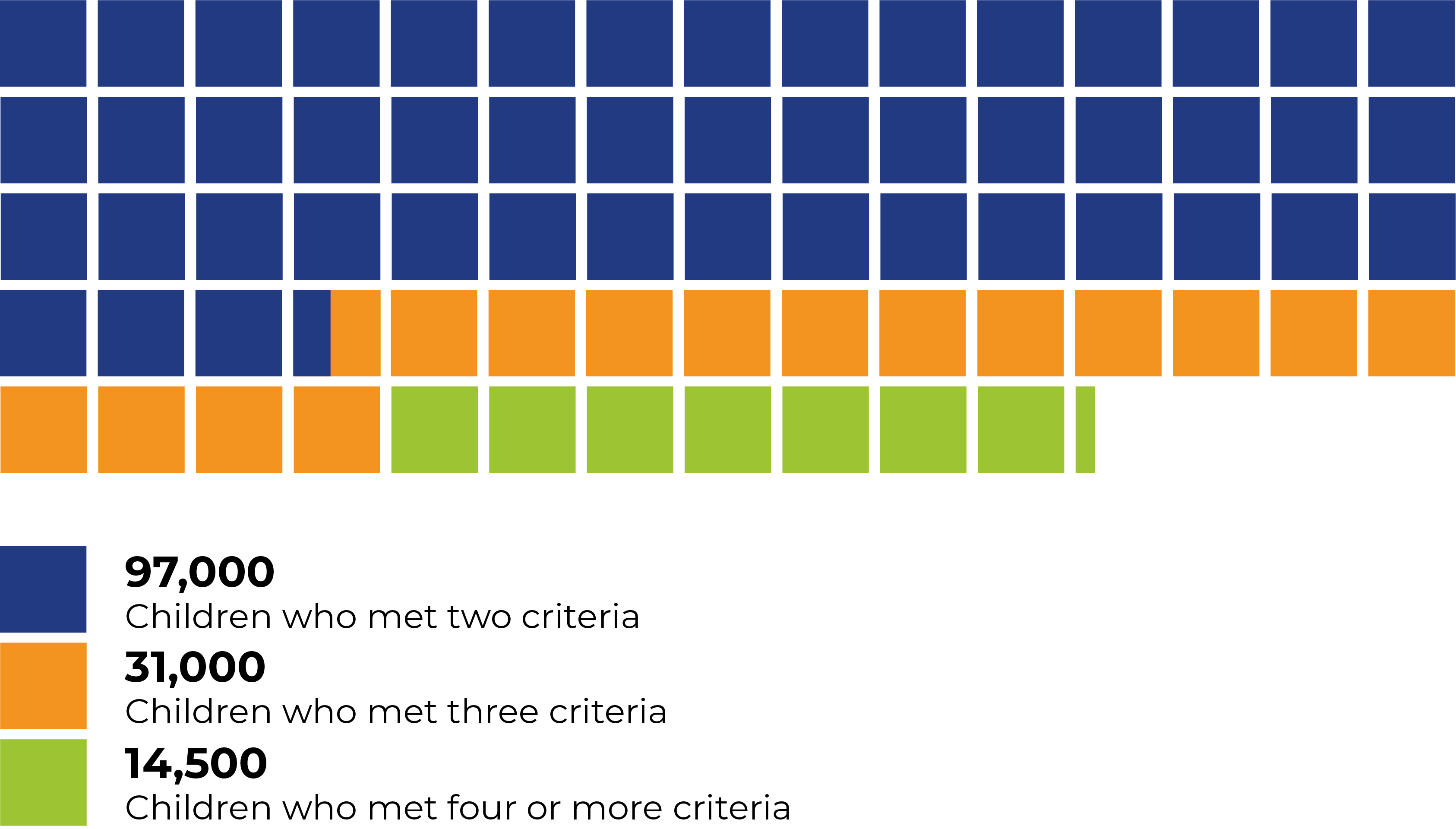

Of this group, 140,000 teens had two or more risks, 46,000 had three or more risks, and 14,500 had four or more risks.

Around 100,000 teenagers were receiving high-cost statutory support in 2017/18, defined as any of the following:

- Being in care during the year

- Being on a child protection plan during the year

- Having an education, care and health plan (EHCP)

- Being enrolled at PRU throughout the whole year

While these groups are important in themselves, we are particularly concerned about the subset of children with additional needs who may not be receiving the right level of help and become disengaged from the systems supposed to support them. We describe these children as ‘falling through the gaps’.

- We define this as children who:

- Have multiple CIN referrals during the year but do not end up on a CIN plan

- Have SEND and also multiple exclusions from school during the year

- Have a permanent exclusion but do not enter a PRU during the year

- Are in care and living in an unregulated placement

- Are in care and have multiple placement changes during the year

- Have a permanent exclusion

- Have high levels of unauthorised absence

- Drop out of the school system in Year 11

- Miss at least an entire term of school in the previous two years

- Are in care but go missing from their placement multiple times in a year

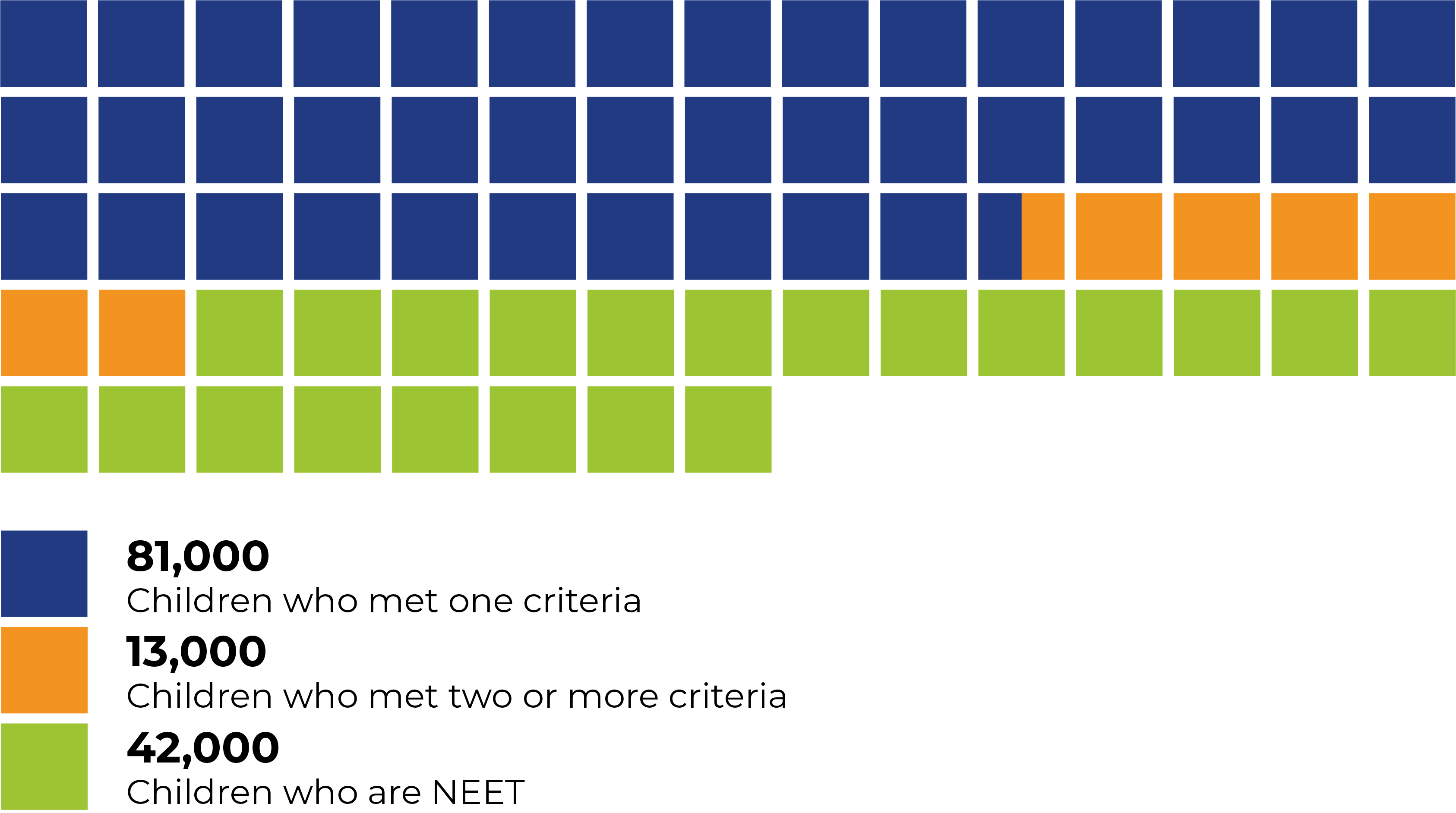

In 2017/18 around 81,000 teenagers aged 13-17 in England met at least one of these criteria, including 13,000 who met two or more of these criteria.

This does not include teens who were not in education, employment, or training (NEET) at the time, because they would not have appeared in the datasets that we use. This is a further 42,000 teenagers whom we can also describe as falling through the gaps.

Adding these up, we can see that 123,000 teens in England were falling through gaps in mainstream provision and becoming invisible to services in 2017/18. This is 4 in every 100 teenagers aged 13-17 – in other words, around 1 in 25 teens. These are not estimates but real teenagers, identified by combining datasets from education and children’s social care and seeing where children go ‘missing’ between them.

We have also broken this down by local area. While the national rate of teens falling the gaps was around 4%, in Liverpool, Medway and Blackpool it was over 7%. At the other end of the scale, the rate was below 2.5% in Wokingham, Barnet, Kingston upon Thames, Westminster, Harrow, Richmond upon Thames, West Berkshire and Rutland.

Because of data limitations, this analysis does not include teenagers who may be falling through gaps in other ways – for example, those with untreated mental health needs or involved in gangs but not known to the police. The data on these groups is not available at a local level or in a way that can be matched with the data used here. Therefore the figures in this report should be seen as conservative and partial estimates of the true scale of the issues affecting vulnerable teens.

We have published this data for each local area in the country, including all the risk measures above. These figures can be found in accompanying data tables below. A separate technical report, setting out the full methodology and data sources used to produce these figures, is also available below.