For as long as I have been Children’s Commissioner, I have been talking about school attendance. This is because attendance is not a ‘nice to have’. It supersedes everything else because, as I made clear in The Children’s Plan,i even the most well-executed and evidence-based pedagogy the teaching profession has to offer is no use to a child who is not in school.

Children understand the importance of being in school. When I have asked children about their priorities, they have told me clearly that they want to get a good education and go on to get a good job. They also regularly tell me about the joys of school, what they like to study, and more simply that they like going somewhere to see their friends.ii

That’s why I have spoken so often about attendance, and why I will continue to do so until all the professionals and services working with children treat it as the priority it should be.

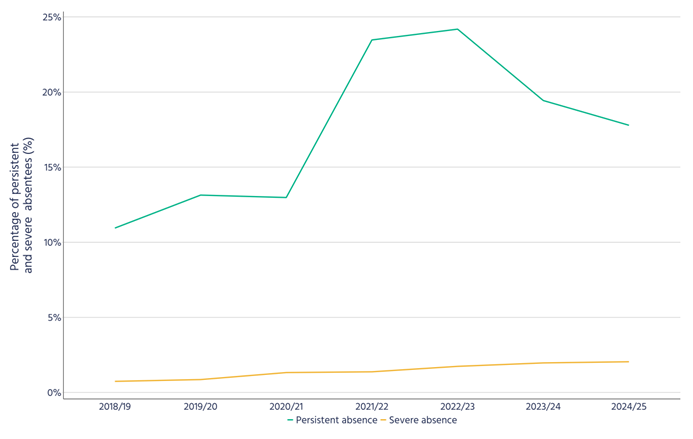

Attendance levels are nowhere near what they were before the Covid pandemic, but there is some movement in a positive direction: 20.1% of pupils were persistently absent – missing 10% or more of school – in the Spring term of academic year 2024/25, down from 21.5% the year before (Figure 1).iii

But things are not moving far or fast enough. The pre-pandemic rate of persistent absence was much lower, at 13.4% in Spring 2018/19.

Figure 1: Percentage of pupils who were persistently and severely absent, Autumn term of 2020/21 to 2024/25

Note: The Spring 2019/20 data collection was cancelled due to the pandemic, and so Autumn term data has been used in this graph to give a more complete historical comparison.

For me, the number of children who are severe absentees is the most concerning feature of current attendance data. Pupils who are severely absent miss at least half of their time at school. It’s not just about numbers on a graph. There are real-world consequences of not being in school, or not being able to be in school. At this level of absence, learning becomes almost impossible, pupils fall behind, and it is incredibly hard for them to fully catch up.

The fact is that severe absenteeism has almost tripled since before the pandemic, and continues to increase every year: from 0.8% of pupils in the Spring term of 2018/19 to 2.2% in Spring 2024/25. This is a profound concern – it means around 160,000 children are missing the majority of their schooling.iv

Since the pandemic, there has been considerable government effort to tackle absenteeism. 2021 saw the introduction of ‘Attendance Hubs’ alongside Department for Education messaging regarding the importance of school attendance. This work was expanded in 2022, and further funding and guidance was issued for schools joining the Hubs programme in 2023.v 2024 saw these hubs open in London, alongside a £15m scheme of direct support for families of persistently absent children.vi The Government’s new RISE teams and hubs will also be tackling attendance, with the first wave of attendance and behaviour hubs already open.vii

I recently used my data powers on schools for the first time, to understand the levels of support available to pupils, and to understand the concerns of school leaders around the country. The result was a state of the nation look at English schools – with a near 90% response rate.

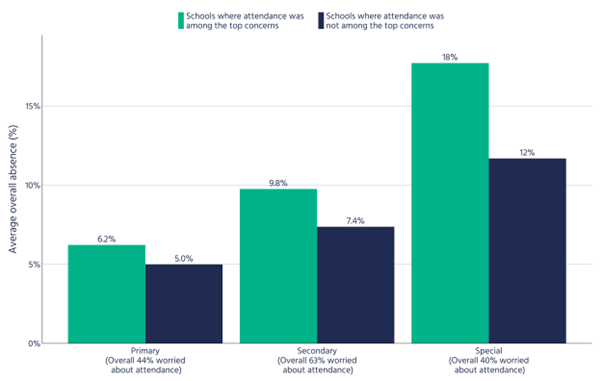

What’s clear is that school leaders are deeply concerned about attendance. Secondary schools and alternative provisions were most likely to say they are worried about attendance (63% and 78% respectively), but there were high levels of concern across the board.

What do school leaders think about attendance?

To create a clearer understanding of how school leaders are thinking about absence, the Children’s Commissioner’s office has compared their level of concern about attendance, as reported in the data they returned, against the actual level of absence in their schools.

There was a general correlation between overall absence and worry about attendance – that is to say, schools with higher absence rates were more likely to worry about absence (Figure 2).

Secondary schools, where absence rates are higher, were most worried about attendance (63%) followed by primary schools (44%).

Special schools, despite having the highest absence rates, were least worried, likely due to the understanding that their pupils’ conditions, whether emotional, physical or learning difficulties, may hinder their ability to get to school.

Crucially, though, across all kinds of setting, those schools that included attendance as one of up to four top concerns had higher average absence rates than those who did not.

Figure 2: Schools worried about attendance, by school type and absence rate across state-funded school population

Note: The Children’s Commissioner’s School Census gathered data for academic year 2023/24, which has been compared here against Department for Education absence data also for 2023/24. Absence rates have been calculated only for schools who responded to the Children’s Commissioner’s Census.

It is right that schools should be interested in attendance, and the fact that the level of worry regarding this issue broadly maps to its prevalence shows that schools are reacting to what is happening within them.

This is important. One of my key discoveries from the Children’s Commissioner’s School Census is how much schools often don’t know about their pupils. We found that:

- 60% of state-funded mainstream schools could not report exactly how many of their pupils had experienced the bereavement of someone important to them,

- 62% could not report exactly how many lived in unsuitable accommodation, and

- 43% could not report exactly how many had a parent or carer in prison.

This data, hearteningly, shows that in the context of national level policy concern about an issue, and clear data (I hear regularly about excellent work that schools and trusts are doing with their attendance data), school leaders are responsive.

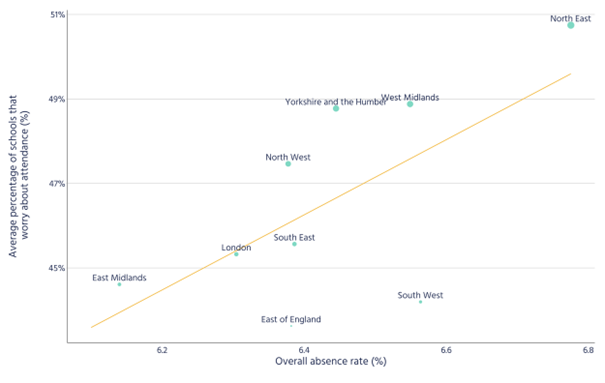

However, Figure 2 does not tell the whole story. The Children’s Commissioner’s office’s additional regional analysis (Figure 3) shows a more complex picture.

Figure 3: Overall absence rate across state-funded school population, by region, and by average percentage of schools that worry about attendance

Note: The Children’s Commissioner’s School Census gathered data for academic year 2023/24, which has been compared here against Department for Education absence data also for 2023/24. Absence rates have been calculated only for schools that responded to the Children’s Commissioner’s Census.

The yellow line represents the average across all regions – regions above this line are disproportionately more worried about absence than would be expected from their actual absence rates, and vice versa for regions below the line.

Some parts of the country seem to worry more about attendance than others. Through the lens of a north-south divide, regions in the north are disproportionately more worried about pupil attendance than those in the south.

Of particular note is the North East, which has both the highest overall absence (over 7.5%) and the most worry about absence (over half of schools are worried about absence). Given that absence in the North East has been a concern for some time, and that the region had the highest overall absence rate, this level of worry is perhaps unsurprising.viii

Some school leaders appear to be less worried than their local rates of absence would suggest they ought to be. The South West is an outlier in this regard, it has the second highest overall rate of absence but is one of the least worried regions (second only to the East of England).

Attendance needs to be everyone’s business. That is why I have called for a fundamental rethink of how children interact with the state in The Children’s Plan. There needs to be a unique ID that works across services, streamlining data collection and access for those that interact with children, helping schools better understand pupils’ barriers to attendance. There is a clear need for additional resources both in and around schools, to not only improve schools’ pastoral practice and to ensure that the community services, from mental health teams to youth workers, are available and able to support children who need extra help to attend.

I know we can do better, because we have done better in the past. It is time for a renewed national effort on school attendance that includes schools, and works with them, but doesn’t place the issue solely at their door – because ultimately, schools can’t fix this alone.

i The Children’s Plan: The Children’s Commissioner’s School Census, Children’s Commissioner, 2025. Link.

ii The Big Ask: The Big Answer, Children’s Commissioner, 2021. Link.

iii Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2025. Link.

iv Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2025. Link.

v Expectations for schools joining attendance hubs, Department for Education, 2023. Link.

vi London school attendance hubs launched, BBC, 2024. Link.

vii 21 behaviour and attendance hub schools named, Schools Week, 2025. Link [1] Pupil absence in schools in England, Department for Education, 2025. Link.