Wednesday’s Spending Review, setting out departmental spending for the 2021-22 financial year, revealed the Government’s key priorities as it continues to grapple with the economic consequences of COVID-19. It coincided with the publication of new economic and fiscal forecasts which predict a drawn-out economic crisis. Unemployment will peak at 7.5% in the middle of next year – double what it was before the crisis – and stay elevated for years to come. The consequences for families with children living in the poorest households are clear.

The story of the Spending Review for government departments is of growth in day-to-day spending across departments, increasing by £14.8 billion (3.8% annual in real terms) compared to 2019/20.

But the story for children is that the help they did get is unlikely to have gone far enough given vastly increased levels of need. It is important to remember the huge impact this crisis has had on children and families, as well as the services they rely on. In some areas, crucial issues were left completely unaddressed by the Chancellor.

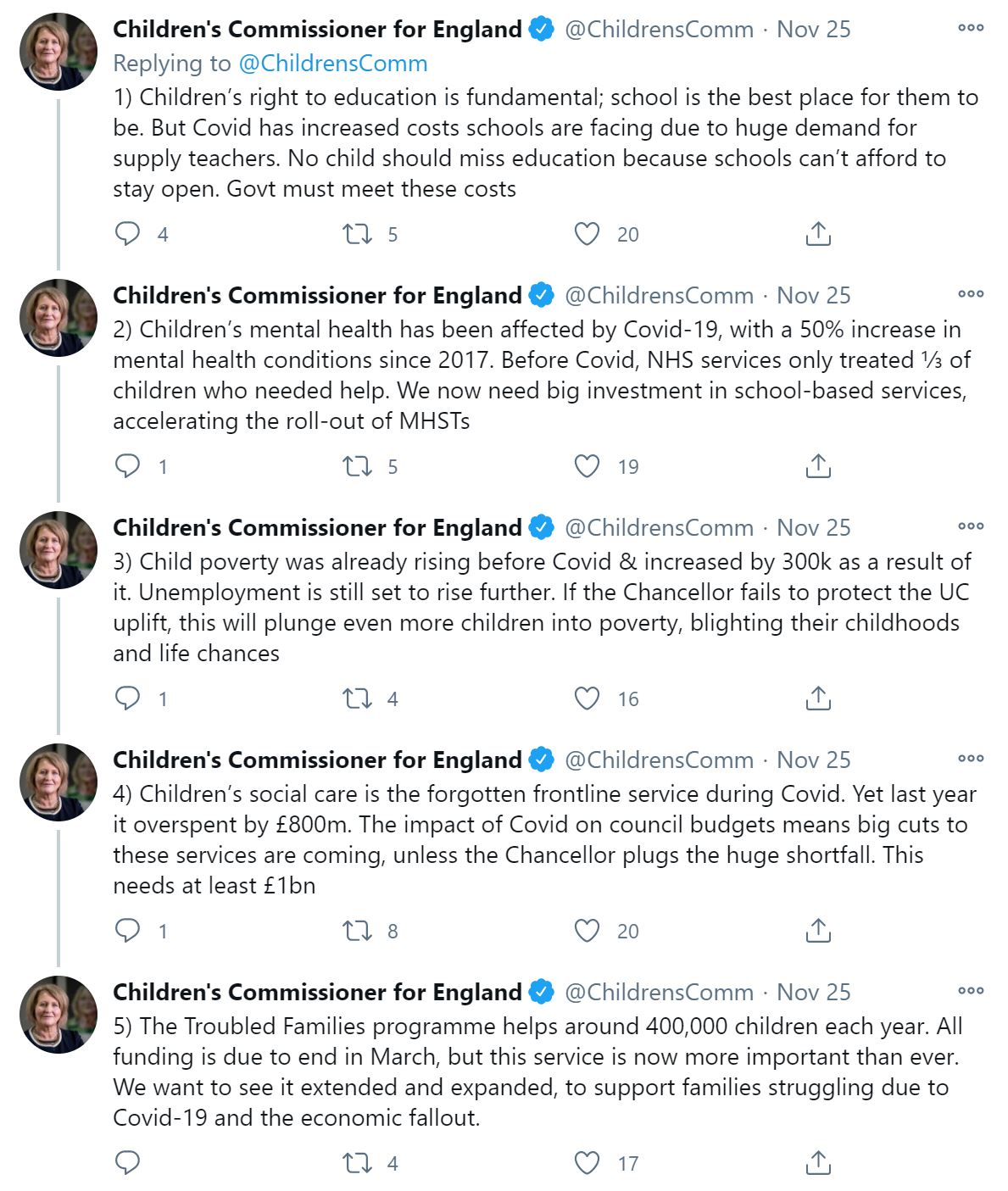

The good news is that a some funding commitments will mean continued help for children who need it most. The Troubled Families programme, which helps around 400,000 children each year, saw its funding extended when it had been due to end in March. However, this programme doesn’t just need to be extended, it also needs to be expanded in order to help the vast numbers of families not being reached by statutory services.

Other funding announcements confirmed previous pledges, including £11.8 million for a cross-Government early years pilots; an additional £25.8 million to increase the value of a Healthy Start Vouchers to £4.25, in line with the recommendations in the National Food Strategy; and a £220 million Holiday Activities and Food programme to meet the Government’s commitment to Free School Meals over school holidays. The £2 billion Kickstart Scheme and £2.5 billion in support for apprenticeships will help young people entering the workforce during a time of economic hardship.

There were also some major funding items where the level of impact on children specifically is as yet unclear but could potentially be significant. For example, the Department of Health and Social Care’s settlement includes £500 million for improvements to mental health services – the majority of which “specialist services for young people, including in schools, and support for NHS workers” according to the Treasury.

All children have a right to an education and keeping schools open is absolutely vital. However, many schools are struggling with staff absences and their supply teacher budgets are already under strain if not exhausted. The Spending Review confirmed that spending on schools will increased in line with the wider growth in spending: an additional £2.2 billion (3.9% higher in real terms than in 2019/20), as announced before the pandemic. The question is how much of this increase will be eaten up by the problems, like staff shortages, that schools are battling with now. The same applies to the £650m catch-up funding announced during the summer, which may end up being used to plug holes in existing teaching rather than its purpose of providing extra tuition for children who have fallen behind.

Funding for local authorities continues to play catch-up with need, rather than get ahead of it. Last year’s £1 billion overall social care grant is continued, with £300 million of new money, £760 million of last year’s lost revenue covered and an additional money through a new local tax (a 3% adult social care precept). This means only a small proportion of the shortfall in children’s social care funding (which we have argued is at least £1 billion a year) is covered directly, and the only option given to local authorities is a significant increase in council tax (which will help wealthier areas more than deprived areas). There is now a real risk that local authorities with high levels of need will have to make further cuts to non-statutory children’s services like early help youth services, leaving more families in the lurch and leading to higher statutory costs in the long run.

There were new announcements for capital spending: an additional £24 million for new secure children’s homes and £300 million for new school places for children with Special Educational Needs. This investment is welcome but must be followed in next year’s multi-year Spending Review with wider investment to tackle the growing crisis in children’s residential care.

It remains to be seen how the £4 billion “Levelling Up” Fund, intended to drive investment in local areas sponsored by local MPs, will impact on children. What we can say it that local areas must consider children’s needs, interests when making proposals.

Significantly, there was no commitment to maintain the £20 increase to Universal Credit beyond April. The costings assume it would last only for 2020/21, resulting in a £6 billion in payments to low-income households that coincides perfectly with the projected peak in unemployment in mid-2021. The loss of around £1,000 a year for these families could result in could result in 700,000 more children being pushed into poverty.

Before the spending review, we set out 5 key things the Chancellor needed to do to protect children.

Of those, the Spending Review delivers (albeit partially) on one: the Troubled Families programme. For others – schools, children’s mental health and children’s social care – the money that has been announced simply won’t be enough to meet increased needs. And on child poverty, the outlook is going to be significantly worse following the Spending Review.

Overall, this was a Spending Review that fell short of what was needed to tackle many of the long-term, generational and systemic problems that affect millions of the most vulnerable children.