Dr Kaitlyn Regehr, author of Smartphone Nation, is an Associate Professor and the Programme Director of Digital Humanities in the Department of Information Studies at University College London. As part of Screen Free Summer, she shares guidance for having a healthy digital diet and prioritising screen consumption. In a previous guest blog she discussed how algorithms shape our digital experience.

When the internet first switched over to commercial providers in the mid-1990s and families began to purchase their first shared family PC, the concept of ‘shoulder surfing’ was introduced. The suggested approach was a way for parents to gently monitor their children’s internet usage, over their kids’ shoulders. That is, while parents sat on the sofa and read the paper, they could glance at the large screen prominently atop a table in the living room.

This guidance evolved with the technology – though only slightly. The concept of shoulder surfing was replaced by screen time to limit the time spent on TVs, computers, tablets, and phones to a set amount of daily usage. Screentime guidance was based on physical health research. This research indicated that children with high levels of television and computer use were more likely to have a higher body mass index. However, because this ‘screen time’ advice was related to physical health concerns it didn’t include robust discussion around the quality or nature of the content and how that might be impacting mental health.

Academics from different fields have put forward the concept of a ‘digital diet’ to help think through the role of digital environments in developing public-health policy.[i] In particular, Amy Orben from MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit at the University of Cambridge has advocated for greater parallels between the study of food and the study of technologies. In her words we need to think about digital consumption in relation to ‘(a) what is being eaten, (b) the amount that is being eaten’ and ‘(c) different food groups . . .’[ii]

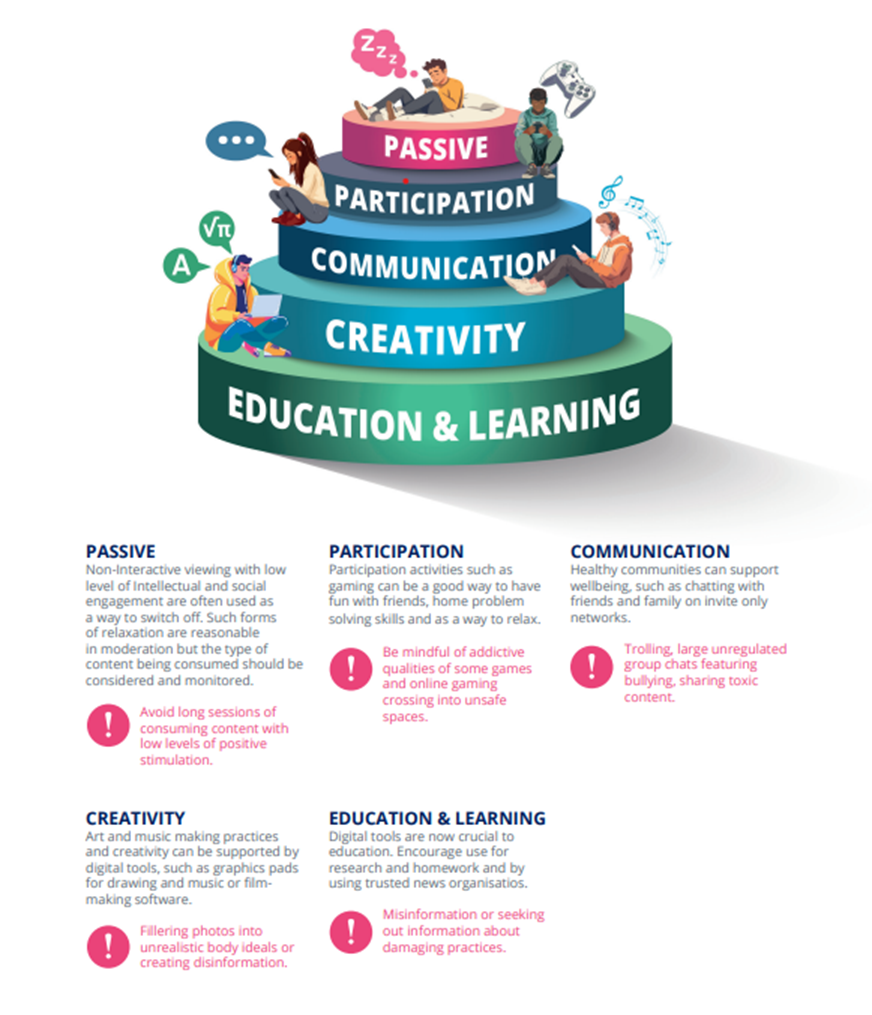

In the same way that not all foods are created equal, we should differentiate between types of content that we are consuming. Building off the work of Dr Amy Orben, my team and I worked with young people to develop a pyramid shape to differentiate between types of digital engagement. It shows how different proportions of each type of screen consumption might support a healthy digital diet.

Here’s how you can try it in your own life:

For a period of a couple of days make notes in a journal (or your notes on your phone) about your screen usage. Write down the following:

- What you opened your phone to do.

- Where you eventually ended up.

- How long the session was.

- You can also write down how your mood was at the end of the session. Did you feel bad, did you feel good?

After a couple of days, if you look back over your phone fed journal and find that you are uncomfortable with the amount of time spent (the quantity) or the overall content and the way it made you feel (the quality) of your consumption, let’s think about changing that.

To help with your journal: both Android and Apple devices also have settings where you can see how much time you spend on your device and on individual apps. You can find instructions about how to change these settings by searching for Screen Time in the Google Help Centre for Android devices and at Apple Support for Apple devices.

My team and I then use a pyramid shape (like the Food Guide Pyramid) [iii] to take a hierarchical approach to the different types of digital engagement. It shows how different proportions of each type of screen consumption might support a healthy digital diet.

Using this guide, you can help young people think about what you want to prioritize with your (and your families) screen consumption. Look over your ‘phone fed journal’ and ask yourself: What categories does my current usage fall into? If your consumption time is high and most of that consumption is sitting at the top of the pyramid, try to move your screen consumption lower down into a more active category.

It’s more than 30 years since the computer became a household device and years since the introduction of screentime guidance. And it now feels high time we integrate new critical thinkings about what we consume by way of screens into public consciousness. Screens that – like food – have become essential to modern life. And screens over which we can have the power to change our relationships – so that we build active, nutritious online engagement. Digital nutrition. A balanced digital diet – for our ‘feeds’.

[i] Orben, A. (2022), ‘Digital Diet: A 21st century approach to understanding digital technologies and development’, Infant and Child Development, 31(1); Internet Matters (2022), ‘Balance Screen Time: How to Create a balanced digital diet’, available at https://www.internetmatters.org/resources/creating-a-balanced-digital-diet-with-screen-time-tips/ accessed 17 October 2024; The Wellbeing Thesis (2023), ‘Digital Wellbeing – How to have a healthy digital diet’, available at https://thewellbeingthesis.org.uk/foundations-for-success/digital-wellbeing-how-to-have-a-healthy-digital-diet/ accessed 17 October 2024.

[ii] Orben, A. (2022), ‘Digital Diet: A 21st century approach to understanding digital technologies and development’, Infant and Child Development, 31(1); Internet Matters (2022), ‘Balance Screen Time: How to Create a balanced digital diet’, available at https://www.internetmatters.org/resources/creating-a-balanced-digital-diet-with-screen-time-tips/.

[iii] Regehr, Shaughnessy and Smales (2025) Digital Nutrition: rethinking digital literacy. In Press.