For most families, having a young child will be a joyful experience. With a new baby, everyone needs help of some sort in order for their child to thrive– whether that’s advice from friends and family who’ve been there before, tips on weaning from health professionals, and, as time passes, subsidised childcare as parents think about going back to work. Some families will need more help. For parents who are, for example, living in poverty or struggling with their mental health, there may be additional challenges to overcome. But it’s not just about individual families – there is also an important role for the state to help children get the best start and help families get ahead. If we want to ensure that no child is left behind there’s no better place for Government to start than the early years.

Many Government departments have something to gain from getting the early years right. New analysis for our report showed that children who are further behind at five are more likely to be struggling with their education at eleven, but also more likely to be excluded and more likely to be involved with social care. So the Department for Education has a clear interest in getting this right.

But we know from recent analysis that 71% of children sentenced in the youth justice system have a learning need and nearly half have been in care, so the Ministry of Justice does too. School exclusion is described by many teenagers as the point where criminal exploitation began, so the Home Office should be concerned as well. Children falling out of the education system are more likely to end up not in education, employment or training (NEET) and on benefits as adults, which will create more pressure for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). Children who are significantly overweight are more likely to be obese as adults, so the Department of Health and Social Care needs to get this right too. The list goes on.

While lots of progress has been made in recent years, with increased entitlements to free childcare, we know that too many children are still not getting the best start in life. Forty-five percent of children living in poverty aren’t at the expected level of development by the time they start school. One in ten children are already obese by age five. And some children are living day to day in dangerous situations and suffering abuse – 50,000 under fives last year were assessed as suffering neglect or abuse.

If we want to address this, we need a comprehensive response in the earliest years of a child’s life that works for all families, and makes sure no child goes without help.

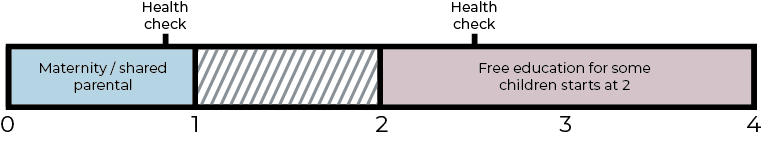

The early years landscape in England has grown up over the decades with a myriad of different Government departments responsible for different parts. This lack of coordination means there are significant gaps – not by design, but by omission. For example, once a child reaches the age of one, parental leave (run by DWP) stops, there are no more health checks (run by PHE) for a year and a half, and no free early education (from DfE) provided. And yet this is a crucial stage for identifying any difficulties, when children should be learning to say their first words and take their first steps.

It also means there are unfair discrepancies, with far more barriers to accessing childcare benefits under DWP’s Universal Credit for low income families than for HMRC’s Tax-Free childcare for higher income families.

But most importantly, as our research shows, it means that children fall through the gaps between different systems, as there is too little coordination to make sure someone is providing help where it is needed. We know that twenty percent of children miss their two and a half year health review. This is a vital opportunity to make sure that all children, particularly the most vulnerable, are identified for any additional support. Yet many Local Authorities do not know if the children that miss out on this check are getting support from anywhere else. And half can’t tell us if those children who need it go on to get extra help after this review.

Many of the building blocks for a system that can deliver a joined up offer of support are already in place. We still have around 2,300 Children’s Centres, even after recent reductions in these services, and there is a commitment in the Conservative manifesto to increase provision of Family Hubs. The Healthy Child Programme is designed to identify every child who might need extra help, and it is currently being refreshed. The Troubled Families programme works with 140,000 under fives, although its future funding is not secure. Nearly 1 million children benefit from free early education.

But a concerted effort is needed from central government to turn this into an ambitious new early years offer, which makes sure that all the different services for families work properly together, and collectively have the capacity to help all those who need it.

This has often been acknowledged by different Governments – in 2018 an Inter-Ministerial Group on the Early Years was announced, chaired by Andrea Leadsom MP, although the recommendations have not yet been published. Her upcoming review into children’s health in the early years will also need to cut across all Government departments. Now is a golden opportunity to build on this work with an ambitious, cross-government early years Green Paper.

Even before coronavirus, we knew that too many vulnerable children were going unidentified and unsupported in their early years. It is vital that as we emerge out of the immediate crisis of coronavirus, we start to rebuild an early years system that stops children falling into crisis and gives every child a better start in life.