As the Children’s Commissioner argued in the Yorkshire Post last week, the right to education has been the defining child right’s struggle of the past 200 years. The aim being that poor children were taken out of the workplace, and into the classroom. In England, it is only since 2013 that all children have had to be in education or training until they become adults, something that has still not been achieved in the other nations of the UK. Article 28 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child recognises the rights of all children to a primary and secondary education. Around the world, an estimated 242 million children currently are currently out of education.

That is why we have to take any deprivation of education extremely seriously. This is happening in England to an unprecedented degree. Up to 8 million children are likely to lose out on six months or more of education as a result of the coronavirus crisis. There are those who dismiss this concern by claiming that children are receiving education at home. However, this is not borne out by the evidence. As the Children’s Commissioner explained in her evidence to the Education Select Committee and my colleague Ed Pennington explains in another blog on this site, there is now very strong evidence that the majority of children at state schools are doing very little formal learning each day. This is particularly so for those in the most deprived communities, but much less so for those attending private schools. This huge disparity is in itself a children’s rights concern: Article 2 of the UNCRC requires that children are not discriminated against because of their circumstance. Yet there is overwhelming evidence that being away from school is more damaging for already disadvantaged and vulnerable children.

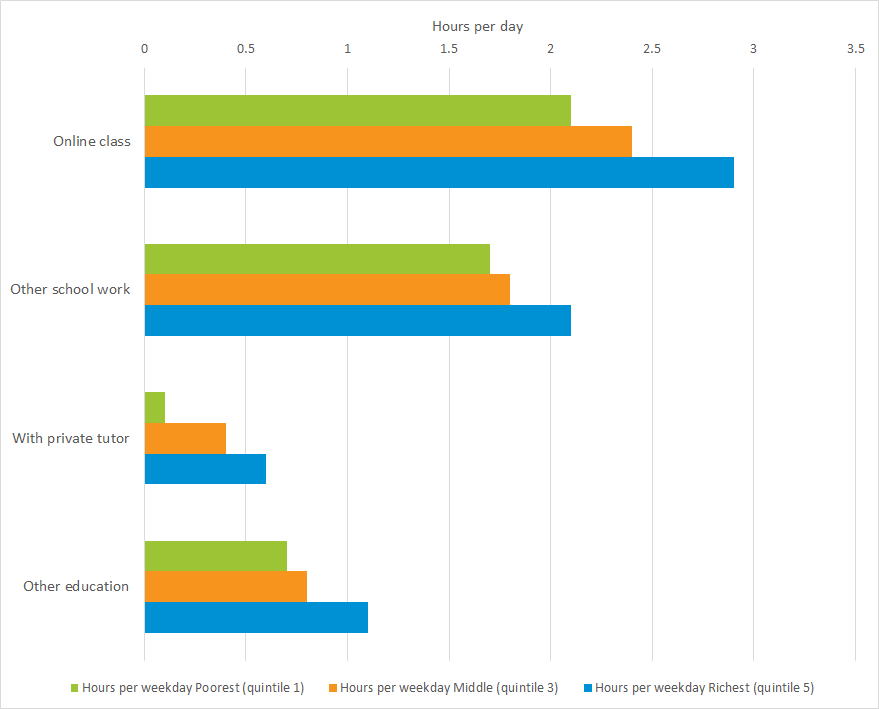

A report from the Insitute of Fiscal Studies found that children from better-off families are spending 30% more time on home learning than are those from poorer families. The following shows daily learning time of secondary school children based on household income.

The UNCRC recognises that schools provide much more than formal learning. Article 29 of the UNCRC mandates that “Education should help develop every child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to the full”. This supplements Article 31 which recognises that “Every child has the right to relax, play and take part in cultural and artistic activities”. These are not things which come from an online tutorial but are nurtured in the classroom and developed in the playground. Of course, many children will get these opportunities, support and stimulation at home. But the point of a right is that all children are entitled to it, and the state has a responsibility to ensure it. That doesn’t mean the state should provide these opportunities instead of families, but it does need to provide them whenever families can’t. This is about the disproportionate impact on those children whose family don’t have the resources – time, knowledge, study space, technology, money – to provide a home environment in which children can develop their interests.

Economically disadvantaged children are not the only ones whose rights are being infringed. Article 23 of the UNCRC makes special provision for those with mental or physical disabilities to “get the education, care and support needed to lead a full and independent life”. In England this is achieved through Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans, as well as in-school support. While some of these children may be returning to school, the vast majority are not, meaning they are missing out on the specialist support that comes with being in school, whether that be provided by teachers, carers or other professionals (such as speech and language therapists).

Finally, we must remember that being at school puts a whole host of protective factors around children which keep them safe from threats outside the home, or recognise the threats to children that exist at home. In doing this, schools form a vital role in delivering Articles 19, 33, 34 and 36, which are all about protection from harm.

All of this has to be balanced against another very fundamental right children enjoy: the right to life. Article 6 of the UNCRC makes very clear that states need to go a long way to preserve this. Therefore where there is a clear health risk to children there is also a clear justification for keeping them away from schools and other facilities. For some children – those with health conditions and disabilities – this is particularly important. But yet an increasing body of evidence has demonstrated that the risk to individual children from Covid-19 are extremely low. This has led Sir Patrick Vallance, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK Government to conclude: “It is very clear that children are at much lower risk of clinical disease and severe disease. For severe disease, the evidence is absolutely clear that they are at very much reduced risk—not zero risk, but very, very much reduced risk. There is also reasonable evidence to suggest that they are at lower risk of getting symptomatic disease or clinically evident disease, so the effect on children is much, much lower”. Even the emergence of a linked inflammatory syndrome, sometimes referred to as Kawasaki disease has not significantly altered this. As Prof Russell Viner, President of the Royal College of Paediatrics concluded “The syndrome is “exceptionally rare. [its emergence] shouldn’t stop parents letting their children exit lockdown”. All this is discussed in our policy briefing on whether children should return to school ‘We don’t need no education’.

This allows us to conclude that for most children (with notable exceptions for children with underlying health conditions which make them more susceptible to the virus), it is, on balance, in their best interests to be back at school. But taking a child-right’s approach doesn’t mean you only consider children. Children are members of society, they benefit from the good of society and their well-being is particularly dependent on the well-being (physically, emotionally and economically) of those adults around them. A child’s rights approach does not mean sending children to school regardless of the consequences to wider society.

Rather, a child’s rights approach is about recognising children as full members of society whose interests need to be considered in and as of themselves. The clearest example is nursery: do we see it as a source of education to benefit children or a means of childcare to support adults working? This is a very live debate when we look at early year’s policy.

To consider how a child’s rights approach would be applied more generally, let’s imagine a Government scheme which offers a holiday activity programme for 20% of children. An approach that considers adults might give the places to those who would most benefit from the childcare – say the 20% of parents most economically productive. But a child right’s approach would allocate the approaches to the children who would most benefit from the places – namely the most disadvantaged. Often, both approaches will combine. When schools were closed for all but a handful of pupils, two groups of children were selected: vulnerable children (whose rights would be most infringed by being out of school) and children of key workers (given the overall benefit to society of their parents being able to work). This approach is entirely consistent with a child right’s approach.

So too were the Government’s initial intentions for easing lockdown. On the 30th April, the Prime Minister announced that education was one of three priorities for easing lockdown, alongside opening up the economy and getting people moving. Education doesn’t need to be the top priority for children’s rights to be considered, but it needs to be there alongside the needs of adults. This was followed up by an announcement that schools would open gradually from the 1st June. This approach considered children’s rights alongside adult’s as part of a suite of measures to re-start the country while keeping the R rate below 1.

But since then progress has stalled, and the focus appears to have moved decidedly away from children. School re-opening will not proceed as planned. There will be no school for Years 2,3, 4, 5, 7, 8 or 9 until September at the earliest. Secondary schools will have only a few weeks of allowing 5% of pupils in. Yet at the same time, plans to re-open the economy and leisure activities which benefit adults are being accelerated. As SAGE minutes show, the opening of schools only has a modest impact on the R rate, yet is being put back, while other measures with similar affect – the opening of all shops, the opening of outdoor visitor attractions and shortly pubs, restaurants and hotels – are being pursued. Suddenly, it appears that the Government has forgotten that children’s best interests are served by them being in school.

In some local areas, the picture is even worse, with local leaders attempting to prevent even the modest re-opening of schools proposed by the Government, while allowing the wider relaxation of lockdown. These areas are asking children to make sacrifices which they are not asking of adults. This is entirely incompatible with a child right’s approach. More problematically still, we have seen some people celebrating the decision not to proceed with a wider opening of schools as a victory over the Government. It was not for the Government’s benefit that schools were re-opening, it was for the benefit of children.

When we look internationally, it is no surprise that countries with a long tradition of upholding children’s rights have prioritised education. For example, Sweden and Iceland who have kept schools open despite closing other parts of the economy, while the Netherlands opened schools for all pupils as part of the first lifting of lockdown. Wales, which will shortly be enshrining the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in domestic law, will be re-opening schools for all pupils before the summer holidays.

It is no good for the Government to point that a few European countries are not letting children return to the classroom until after the summer holidays. On children’s rights we should aim to be out in front, not somewhere in the middle.

So what does a child rights approach mean moving forwards? First, we cannot forget the fundamental rights children have to be in school, and to receive the wider benefits this provides. It cannot become the status quo for schools to remain closed; those looking to keep closed schools must justify why this is necessary for each and every day that they are depriving children of an education. Second, we need immediate and far-ranging plans to help children receive the benefits that come from being in school. This means not just their formal education, but also the opportunity to develop hobbies and interests, to keep active mentally and physically, and to socialise with friends. Finally, where children aren’t able to return to school because they have particular health risks, the state needs to ensure that those children receive these exact same benefits and opportunities through some other means.

The Government must act on these three areas now, if it wants to uphold children’s rights.