Since schools closed to all but a few students in March, millions of children have had to stay at home. While schools started to open in the weeks leading up to the summer holidays, many children did not return to school and will not until September. Given this unprecedented interruption to learning for many children, and with the underlying threat of further lockdown, the Children’s Commissioner’s Office has undertaken preliminary research on the state of home environments and family relationships.

This research is based on the second wave of Understanding Society’s COVID survey, conducted over 6 days at the end of May and beginning of June. The survey sample covers 11,974 respondents in England with 6,577 children. This follows on from our previous look at homeschooling statistics from the same source.

The findings show that while most homes provided a comfortable and welcoming place for children during lockdown, many children were staying in unsatisfactory conditions or saw personal relationships deteriorate.

Home environment

During lockdown, most children (92%) in England had access to a private garden – in line with ONS analysis on Ordnance Survey map data. In London, however, this figure drops to 66%. This leaves 1,137,820 children in England without a private garden – 723,300 children in London alone.

The same data also shows that there are many children in England without access to any outdoor space at all. This includes those without a private garden, balcony and/or shared, communal plot from their home – equivalent to 253,000 children in England (2%) or 106,000 (5%) in London. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) children are also four times as likely to have no access to outdoor space compared to those from white backgrounds.

| Type of outdoor space | BAME | Non-BAME |

|---|---|---|

| Private garden | 78.3% | 91.5% |

| Shared garden | 4.9% | 3.3% |

| Balcony | 6.5% | 2.7% |

| Rooftop garden or terrace | 0.7% | 0.4% |

| Other outdoor space | 5.5% | 3.4% |

| No outdoor space | 8.1% | 2.1% |

Note: Respondents were asked to select all types of outdoor spaces available to them at home. As a result, percentages may not sum to 100 as households can have access to more than one type of space.

Unsurprisingly, children in poverty also have less access to outside space. In households earning less than 60% of pre-pandemic median household income (£514 per week), 6% of children had no access to any outdoor space.

| Type of outdoor space | Non-Low income | Low income |

|---|---|---|

| Private garden | 91.8% | 81.9% |

| Shared garden | 2.9% | 7% |

| Balcony | 2.9% | 3.9% |

| Rooftop garden or terrace | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Other outdoor space | 3.2% | 5.7% |

| No outdoor space | 2.1% | 5.9% |

Furthermore, the analysis shows that 31% of children in England (4.2 million) lived in homes that did not have enough desk space for everyone working or studying from home. This percentage increases to 37.5% for children living in low income households.

| Enough deskspace? | Non-Low income | Low income |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 68.8% | 62.5% |

| No | 31.2% | 37.5% |

Note: Having enough desk space is defined by whether everyone in the household, whether working or studying from home, has their own desk or table to work at.

Family relationships

In the second wave of their COVID survey, Understanding Society asked respondents additional questions on parent-child relationships in the home. This included asking parents about their relationships with their children and whether they thought these had improved or worsened since lockdown began.

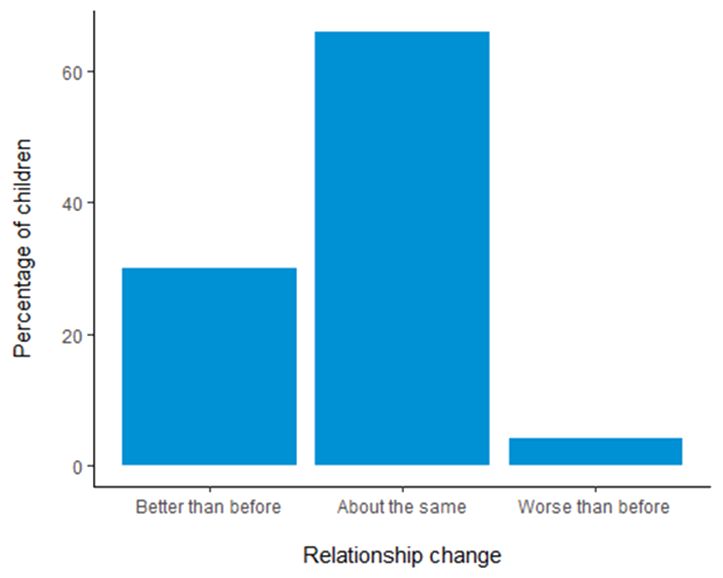

In most households, family relationships (as reported by adults) have largely strengthened or remained the same since March. About 30% of children lived in households where the responding adult said that parent-child relationships had improved.

However, this still leaves 506,000 children (4%) in England who live in homes where parent-child relationships have worsened. Compared to their more affluent peers, low-income children were almost 1.7 times more likely to be in households where relationships had deteriorated – a finding that holds true after controlling for demographic factors and the age of the youngest child.

| Relationship change | Non-Low income | Low income |

|---|---|---|

| About the same | 64.2% | 63.1% |

| Better than before | 31.4% | 30.9% |

| Worse than before | 4.3% | 6% |

| Age of youngest child | Better than before | About the same | Worse than before |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 0-4 | 28.7% | 67.2% | 4% |

| 2. 5-15 | 31.5% | 63.8% | 4.8% |

| 3. 16-18 | 19.8% | 77.7% | 2.5% |

Overall, these figures show that while staying at home has generally been comfortable for most children, 1 in 3 children live in homes without adequate space to work. This highlights the importance of policies that provide children with functional, socially distanced work spaces in the community when home-working environments are unsuitable. Furthermore, though family relationships have largely improved during lockdown, a small number of children live in homes where relationships have worsened. Therefore, it is also crucial to continue providing community and mental health support to families disproportionately affected by lockdown.