Children’s lives changed beyond recognition when full lockdown began on 23rd March. With schools shut to the majority of pupils, the regular rhythms of childhood and adolescence – from school runs and playtime, to exams, celebrations and graduation – were put on indefinite hold.

Anecdotally, we know that many children struggled with the demands of home learning and with loneliness after weeks of social isolation. Vulnerable children faced real hardship as a result of Covid-19, in particular children in care and custody, those with disabilities or mental illness, those at risk of abuse or without a permanent home. However, for many children with a stable home environment, lockdown brought some welcome respite from the everyday stresses of school, bullying and peer pressure.

As the Covid-19 crisis unfolded, the Children’s Commissioner’s Office wanted to understand in greater detail how school closures and weeks at home had affected children’s levels of stress and anxiety. We therefore conducted surveys of around 2,000 young people aged 8-17 in England in March and June, to establish the frequency and causes of children’s stress in lockdown.

How often did children feel stressed during lockdown? (June survey)

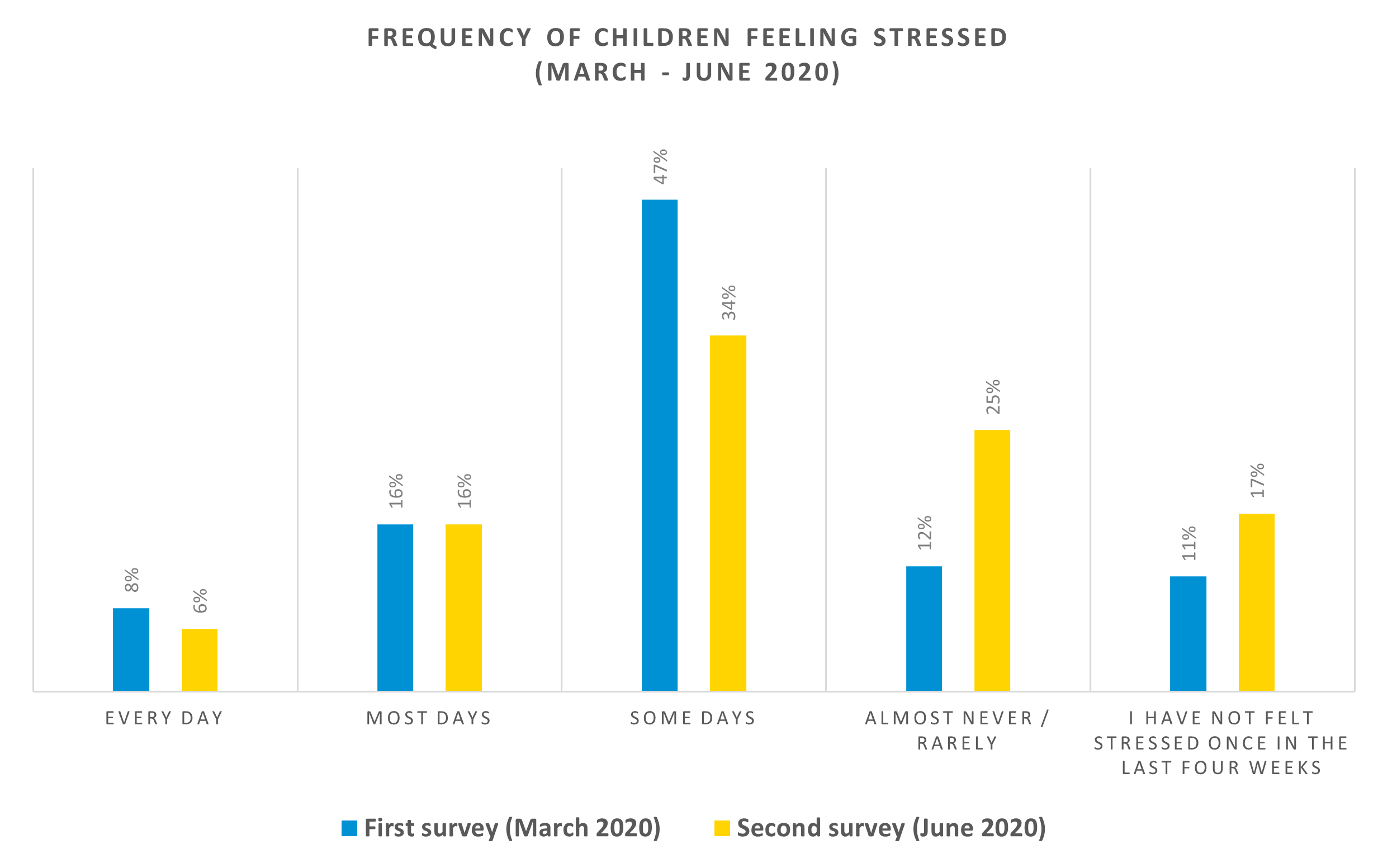

Contrary to what may have been expected, the surveys found that many children felt stressed less frequently as lockdown progressed. The percentage of children feeling stressed some of the time decreased from 47% to 34% between March and June 2020, while the percentage of those feeling ‘rarely or ‘never’ stressed rose substantially from 23% to 42%.

The reason behind the fall in some children’s stress levels through lockdown is still open to speculation. Some insight comes from children’s free text answers to our question ‘what makes you feel stressed?’. In the first survey, answers were diverse, including school, big crowds, anxieties about appearance, bullying, gaming and even allergies. In the second survey answers almost exclusively centred around coronavirus, with very few exceptions. We can hypothesise that the elimination of these ‘extra little’ everyday worries left some children feeling less stressed during the pandemic.

Another answer may be found in the timing of our first survey (13-27th March), a period of particular public crisis and confusion as lockdown was announced and schools closed indefinitely. The overall reduction in stress may have been a natural result of lockdown becoming ‘normalised’, and therefore less of a source of stress for most children.

However, it is worth noting that the number of children reporting persistent stress – everyday or most days – remained consistent between the surveys, around 22-24%. Children whose parents were unemployed at the time of the June survey were most likely to experience persistent stress, 29% of whom reported feeling stressed most or every day.

Persistent stress is a predictor for common mental health diagnoses – including depression, anxiety, OCD and panic disorder. Persistent stress, and wider mental health problems, unlike ‘small, everyday’ stresses, would not necessarily have been eliminated by lockdown. In fact, YoungMinds found that the coronavirus pandemic worsened the condition of 80% of young people with a history of mental health needs. Therefore, it should perhaps be no surprise that our surveys found a consistent number of children experiencing persistent stress at the beginning and at the end of lockdown.

What caused children to feel stressed during lockdown?

School

“Doing my schoolwork at home. I find it harder than in the classroom. There are lots more distractions. It’s noisy having my sister around. My parents are stressed because they have to work and teach us. I miss my friends.” Girl, 8

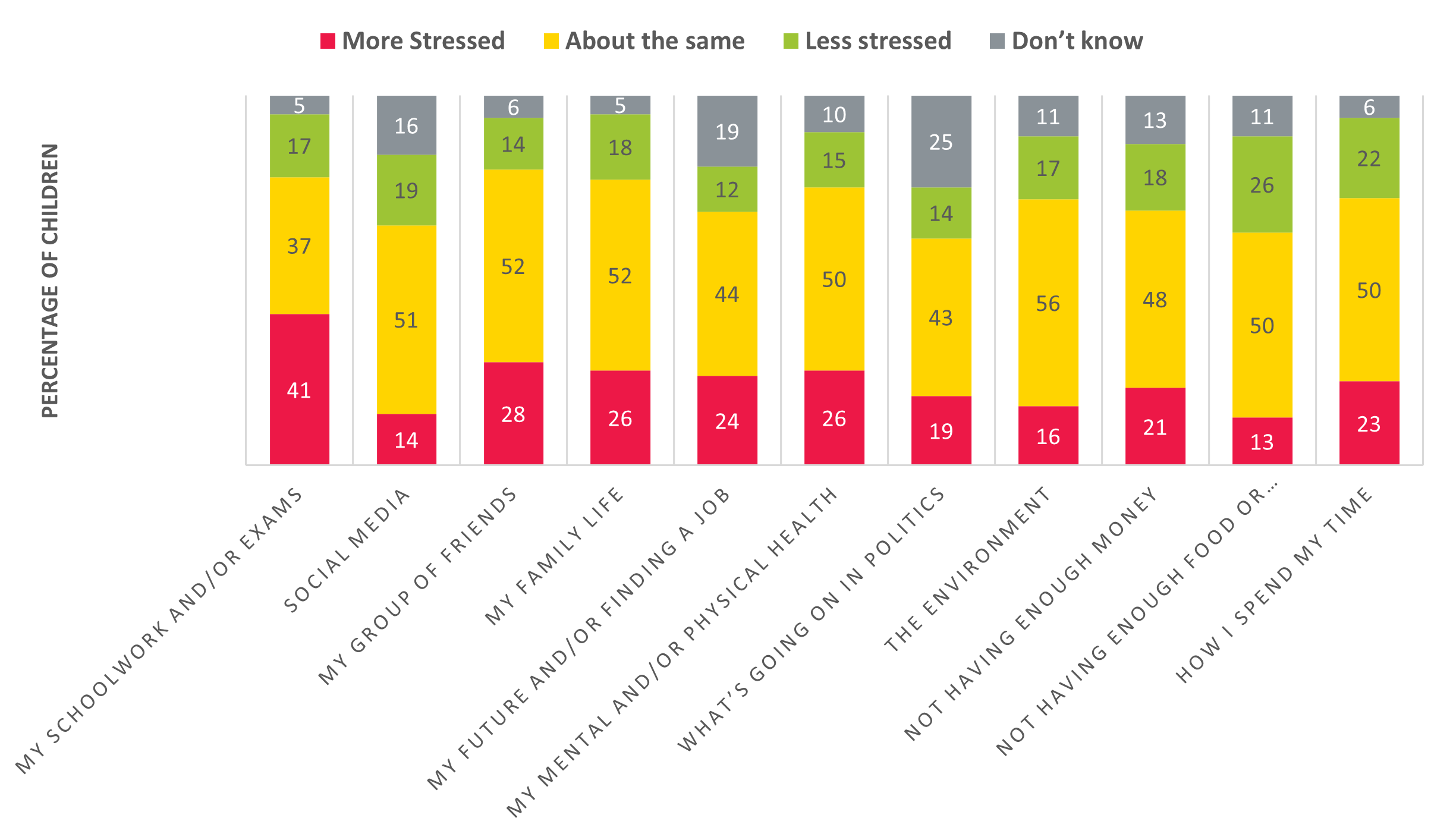

The greatest reported increase in stress during lockdown came from worries about school. 41% of children reported feeling more stressed about schoolwork and exams since schools closed.

Children were worried about their workload and some said they received little support and guidance from teachers. Older teenagers wrote about the stress caused by missing out on exams and the risk of not receiving the grades they felt they deserved.

“I could not take my GCSEs and my results have been taken out of my hands. It feels like a violation and I am not in control of my destiny.” Girl, 15

Our survey suggests that girls were particularly prone to experiencing stress about missed school. When asked in June about what had made them feel most stressed over the past eight weeks, girls were statistically more likely than boys to select school related activities including ‘missing schoolwork’, ‘missing education’ and ‘exams’.

Health

While young people are at less risk of developing serious illness from Covid-19, children nonetheless felt stressed as a result of the secondary health implications of lockdown. Boys in particular reported stress about health and being unable to do sports or other physical exercise.

“Losing my physical output on football as that was somewhere I could just focus on football and not think about anything else going on in my life and just let everything go and now obviously I can’t do that it’s been hard” – Boy, 16

We did not ask an explicit question about mental health. However, the number of children who wrote about ‘feeling trapped’, ‘being locked’ and ‘feeling stuck’ was striking.

“I feel as though the world is ending and I want to scream but I can’t I’m trapped in my own head and still forced to do work” – Girl, 17

Children with parents in unskilled manual professions (e.g., a supermarket worker) were statistically more likely to be caused stress due to worrying about their health or getting ill (40%) than all other social grades, except higher managerial professions.

Social and family life

Most children today have the ability to maintain active social lives online. Lots of children play games and keep in touch with friends and family around the world, in a way that wouldn’t have been possible in generations before. Yet it is clear that children felt the strain of isolation and the lack of face-to-face, human contact with friends and loved ones outside the immediate household. In June, 50% of children reported feeling stressed about not being able to see their friends or relatives in person.

“I can’t see my friends and we’ve planned lots of fun things that I can’t go to or do” Girl, 13

Notable, also, were the number of children who wrote about feeling ‘unable’ or ‘incapable’ of participating in normal activities.

“A lack of being able to go out and play football or go to the cinema” Boy, 15

“Worried I won’t be able to catch up or I’ve missed too much” – Boy, 8

“Been stuck at home and not able to go out to play or meet friends” – Girl, 15

Teenagers also reported feeling stressed about cancelled events and missed milestones, such as graduations and summer celebrations.

“Missing out on big important milestones” – Girl, 15

Jobs, finances and the future

The broader consequences of growing up in a global pandemic remain to be seen. However, it is clear that many children already perceive a future that is confusing and uncertain. Evidence from previous recessions demonstrates that young people bear a disproportionate burden of job losses and economic hardship; there is no reason to suspect that the Covid crisis will be different. In June, the Trussell Trust reported a ‘soaring’ 89% increase in need for emergency food parcels during April 2020 compared to the same month last year, including a 107% rise in parcels given to children. The number of families with children receiving food parcels in April 2020 doubled compared to the same period last year.

As the economic fallout of Covid-19 begins to take shape, young people will also have a significantly harder time breaking into the job market – an experience that is likely to ‘scar’ this generation’s employment prospects for years to come. Young people are over-represented in sectors including retail, hospitality and travel, all of which were deliberately shut down to curb the spread of coronavirus. Our briefing on young apprentices published earlier in the year found that apprenticeship starts for under-19s were a quarter of last year’s numbers (1,040 in 2020, down from 4,020 in 2019).

Given this backdrop of soaring youth unemployment, it comes as no surprise that our June survey found 1 in 4 children were feeling stressed about the future or finding a job. The proportion of young people reporting stress related to jobs and the future rose with age, to over half (53%) of 17-year-olds.

“Pressure of school exams and worrying about getting a job” – Boy, 17

“I feel stressed because I am very uncertain on the future.” – Girl, 17

Conclusion

Our surveys suggest that the elimination of smaller, ‘everyday’ worries meant that some children’s stress levels decreased during lockdown. Smaller stressors – including anxiety about appearance, bullying and tests – seem to have given way to a more singular focus on Covid-19 and its secondary effects on schoolwork, health, social lives and employment opportunities. Whether the stress from these secondary effects of the pandemic will intensify in the coming months and years remains to be seen.

However, this overall reduction in stress was not universal. As the Children’s Commissioner has highlighted over the past months, the Covid-19 crisis has exposed the gulf between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged children. One in five young people reported persistent stress during lockdown. These children may have been suffering intensified pressure on their mental health, or confined in chaotic home environments. We must ensure that the needs of these children are not overlooked as we enter the next stages of the Covid-19 pandemic.

To read more about the findings from these surveys, see our technical report

The Children’s Commissioner’s Office worked with OPINIUM to survey children.

OPINIUM is a strategic insight agency that works with organisations to define and overcome strategic challenges – helping them to get to grips with the world in which their organisations operate.